Under construction: Engineering the Bay Bridge

For Part 1 of this story, see the March 2011 story Superstructure rising.

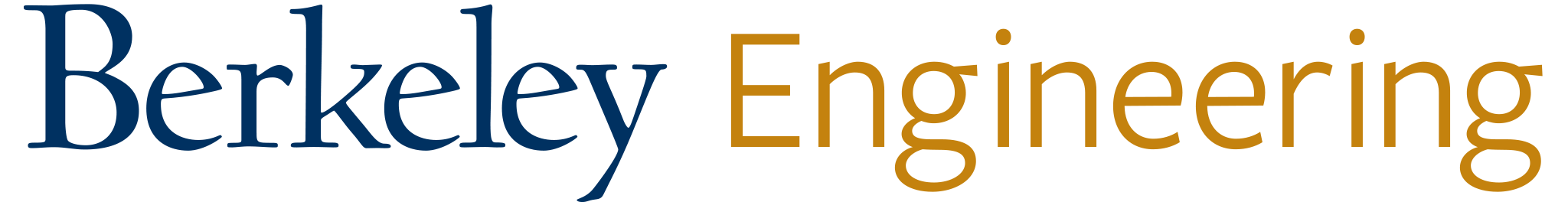

Slated to open in late 2013, the new eastern span of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge is meant to do what the old one didn’t: withstand a major Bay Area earthquake (7.0 or greater), sustain only limited damage and quickly admit emergency vehicles and traffic. It must deliver a performance to match its “lifeline” designation, adopted by the state legislature not long after the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989.

It’s also a lifeline for Marwan Nader (M.S.’89, Ph.D.’92 CE)—because he’s bet his career on it. Beginning in 1997, when he first got involved in the project as lead design engineer at renowned structural engineering firm T.Y. Lin International, he’s defended the sometimes controversial self-anchored suspension (SAS) plan; weathered waves of criticism and cost overruns; survived political tugs-of-war, delays and project kills; and still is working on it, adjusting the design to support the contractors as they erect the structure.

After the Loma Prieta quake, the Bay Bridge was deemed a ticking time bomb. In the years after the historic 6.9 temblor, state transportation officials debated whether to retrofit or replace the bridge. The western span could be retrofitted, Caltrans engineers determined. In 1997, after a lengthy economic and structural analysis, then-Gov. Pete Wilson approved replacement of the eastern span, citing longevity of 100 years or more with a new structure, as opposed to 30 with the existing span.

Caltrans entertained bids and selected two semi-finalist designs from two separate teams in a joint venture between T.Y. Lin International and Moffat & Nichol Engineers to compete for the winning design.

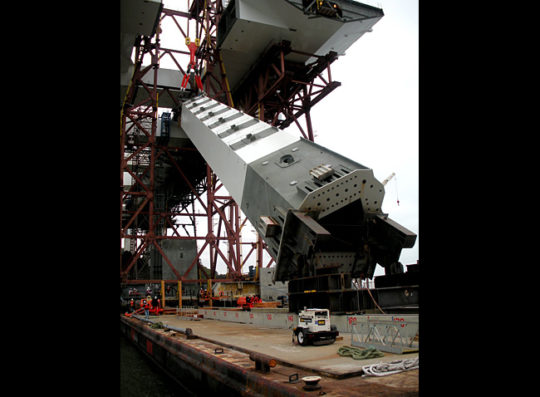

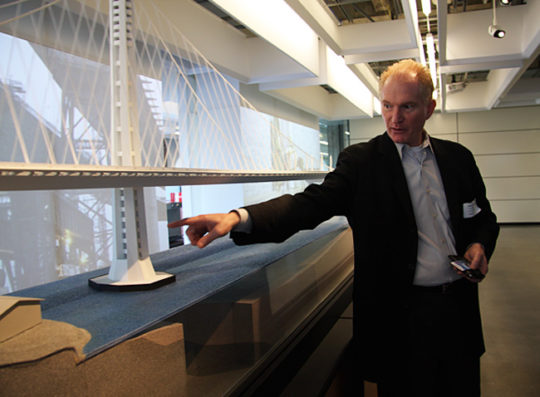

Nader led the single-tower SAS team. The challenge? Marry the precise aesthetic specifications dictated by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission with the stringent seismic performance required by Caltrans. Specifically, find a way to stabilize a single tower in a major earthquake so it wouldn’t snap off like a light pole. Remembering his Ph.D. adviser Egor Popov’s research involving shear link beams in eccentric-braced building frames, Nader realized he could split the tower into four slender shafts and connect them up the height with two-meter-long shear links, maintaining a single tower look. Seismic performance analysis outcomes proved excellent.

Nader’s team built a physical model and took it to the final competition. Nader was on cloud nine when the single-tower SAS design won the contract. “Not only was my team’s design selected,” he said, “but I knew it was going to become a reality. It was a fantastic moment.”

In early 1999, Nader assembled his team of engineers to meet with Caltrans officials and agreed to deliver final plans by mid-2001. They logged 60- and 90-hour workweeks, sleeping in their offices and putting personal lives on hold.

But, outside of T.Y. Lin International, all did not proceed as planned. A political controversy erupted over the alignment of the new span. Questions over right-of-way access to Yerba Buena Island put the Navy in conflict with Caltrans. Oakland and San Francisco raised objections. A bike and pedestrian path was studied, debated and incorporated. And critics raised concerns over the bridge’s performance during a major earthquake.

But Nader has remained confident in the bridge’s seismic integrity. T.Y. Lin International used industry-standard ADINA general-purpose finite element software to run three different seismic performance analyses: time history, pushover and local detailed analyses. “This bridge has been scrutinized more than any other structure I’ve worked on,” the long-time bridge engineer says. “The testing and performance are sound.”

Nader’s team delivered final plans on schedule and continued to tweak the design through more delays and setbacks. In 2004, when a single construction bid came in, escalating construction costs had pushed the price tag far too high. Political controversy and public outrage temporarily halted the project again. Construction finally began in 2006, four years late.

“This project eats up human beings,” says Brian Maroney, deputy director of the Toll Bridge Program at Caltrans, who has worked on the Bay Bridge upgrade since 1995. “A lot of people have fallen by the wayside. But Marwan Nader has taken a few hits and is not a quitter. He has done some great things for us. UC Berkeley has reason to be proud of him.”

Nader is already working on new bridges in Africa and the Middle East but admits there will be a vacuum in his life after the new Bay Bridge opens in 2013. “No question about it,” he says, “It’s once in a lifetime.”